Braving the Red Sea: As Abq Jew mentioned just last year (see Swimming With Nachshon), we Jews remember the bravery of Nachshon ben Aminadav as we observe the Seventh Day of Passover.

On the Seventh Day of Passover - the anniversary of the day when this glorious event happened - we again read the story of the Crossing of the Red Sea and the ensuing celebrations.

|

| Nachshon ben Aminadav David Brook |

While everyone who has seen The Ten Commandments knows that Moses and his staff (including The Holy One, Blessed Be He) parted the waters of the Red Sea - we Jews also remember Nachshon, who was the first to step in when the Egyptians were chasing us.

And Nachshon didn't just stick a toe in. He continued walking until the water was up to his neck. Then and only then did the Red Sea part, allowing us Children of Israel to cross on dry land.

|

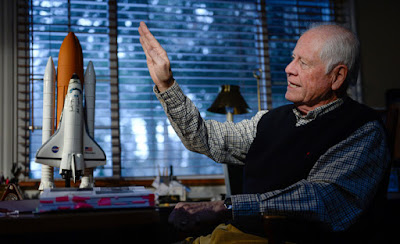

| Mr. McDonald recounts the 1986 Challenger launch in 2016. (Francisco Kjolseth / Salt Lake Tribune) |

Allan J McDonald died earlier this month, and Abq Jew could not let his passing go (at least, on TV news) almost entirely unnoticed.

If you don't remember his name: McDonald was the senior on-site representative of his company, contractor Morton Thiokol, who refused to sign off on the January 28, 1986 launch of the Challenger space shuttle over safety concerns.

Superb obituary writer Emily Langer wrote in The Washington Post:

Allan McDonald, engineer and whistleblower in the Challenger disaster, dies at 83

Allan J. McDonald, a rocket scientist and whistleblower who refused to sign off on the launch of the Challenger space shuttle over safety concerns and, after its explosion, argued that the tragedy could have been averted had officials heeded warnings from engineers like himself, died March 6 at a hospital in Ogden, Utah. He was 83.

Mr. McDonald was in Cape Canaveral, Fla., at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, where the Challenger was set to take off. He oversaw the engineering of the rocket boosters used to propel the shuttle into space. Among colleagues, the New York Times reported, Mr. McDonald had a reputation as one of the most skilled rocket engineers in the country.

It was unseasonably cold in Florida, with weather forecasts predicting that temperatures might drop as low as 18 degrees Fahrenheit in the hours before the Challenger was scheduled to lift off. That cold snap became the crux of vociferous debate among Mr. McDonald and other engineers, Morton Thiokol executives and NASA officials about whether the mission should go forward.

Citing the cold, Mr. McDonald insisted that takeoff be postponed, according to accounts of the deliberations that later emerged in news reports. A critical component of the rocket booster was the O-ring, a rubber gasket that served to contain burning fuel. Because of their composition, O-rings were highly vulnerable to temperature drops, and engineers warned that their effectiveness could not be guaranteed below 53 degrees Fahrenheit.

“If anything happened to this launch, I told them I sure wouldn’t want to be the person that had to stand in front of a board of inquiry to explain why I launched this outside of the qualification of the solid rocket motor,” he would later testify.

Protocol required the senior engineer to sign off on the launch. When Mr. McDonald refused, his supervisor signed for him. The Challenger lifted off at 11:38 a.m. on Jan. 28 and disintegrated approximately 72 seconds later, its remains streaking across the sky.

“My heart just about stopped,” Mr. McDonald later said in a public lecture, according to the Commercial Dispatch of Columbus, Miss.

Mr. McDonald was present at a closed session of the commission — watching from what he called the “cheap seats” — when he heard what he considered misleading testimony by a NASA official about the debate leading up to takeoff.“I was sitting there thinking, ‘That’s about as deceiving as anything I ever heard,’ ” Mr. McDonald said in an interview aired on NPR.

“So I raised my hand. I said, ‘I think this presidential commission should know that Morton Thiokol was so concerned, we recommended not launching below 53 degrees Fahrenheit. And we put that in writing and sent that to NASA.’

I’ll never forget Chairman Rogers said, ‘Would you please come down here on the floor and repeat what I think I heard?’ ”

|

| Engineer Allan J. McDonald testifies before the presidential committee investigating the Challenger space shuttle disaster in 1986. (Charles Tasnadi/AP) |

Mr. McDonald was demoted at Morton Thiokol after his testimony, then reinstated after Congress moved to end the company’s federal contracts if he was not returned to his job.“I really expected to be going out the door,” he later recalled.

“And I would have, if it had not been that the presidential commission and certain members of Congress found out about it and really read the riot act to the management of my company. That saved my job, frankly.”

After his reinstatement at Morton Thiokol, Mr. McDonald played a principal role in a redesign of the booster rockets. He retired in 2001 as a vice president at the company.

With James R. Hansen, he wrote the book Truth, Lies, and O-rings: Inside the Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster (2009) and spoke frequently to scientific, corporate and government audiences about the role of ethics in professional life.He often cited an aphorism with particular resonance for him.

Regret for things we did is tempered by time.Regret for things we did not do is inconsolable.

For more than 30 years, Bob Ebeling carried the guilt of the Challenger explosion. He was an engineer and he knew the shuttle couldn’t sustain the freezing temperatures. He warned his supervisors. He told his wife it was going to blow up.The next morning it did, just as he said it would, and seven astronauts died.Since that tragic day, Ebeling has blamed himself. He always wondered whether he could have done more.

His daughter, Kathy Ebeling, said he had even entertained bringing his hunting rifle to work Jan. 28, 1986 to threaten NASA not to launch — that’s how certain he was that the shuttle was going to explode.

“I think that was one of the mistakes that God made,” Ebeling told NPR. “He shouldn’t have picked me for the job. But next time I talk to him, I’m gonna ask him, ‘Why me? You picked a loser.’ ”But listeners didn’t hear a loser. And they sent hundreds of e-mails and letters to NPR and directly to Ebeling telling him so ....His daughter, reached at their Utah home, said she’s been reading him the letters. Engineering teachers said they use him as an example of good ethical practice. Professionals wrote that because of his example they are more vigilant in their jobs.But there was one person that made him finally start to believe he wasn’t to blame.Allan McDonald, who was Ebeling’s boss, reached out after the NPR interview aired to tell him that he had done everything he could have done to warn them, including calling Kennedy Space Center to try and stop the launch.

let us remember Nachshon's bravery.

And may we live up to the example he set.